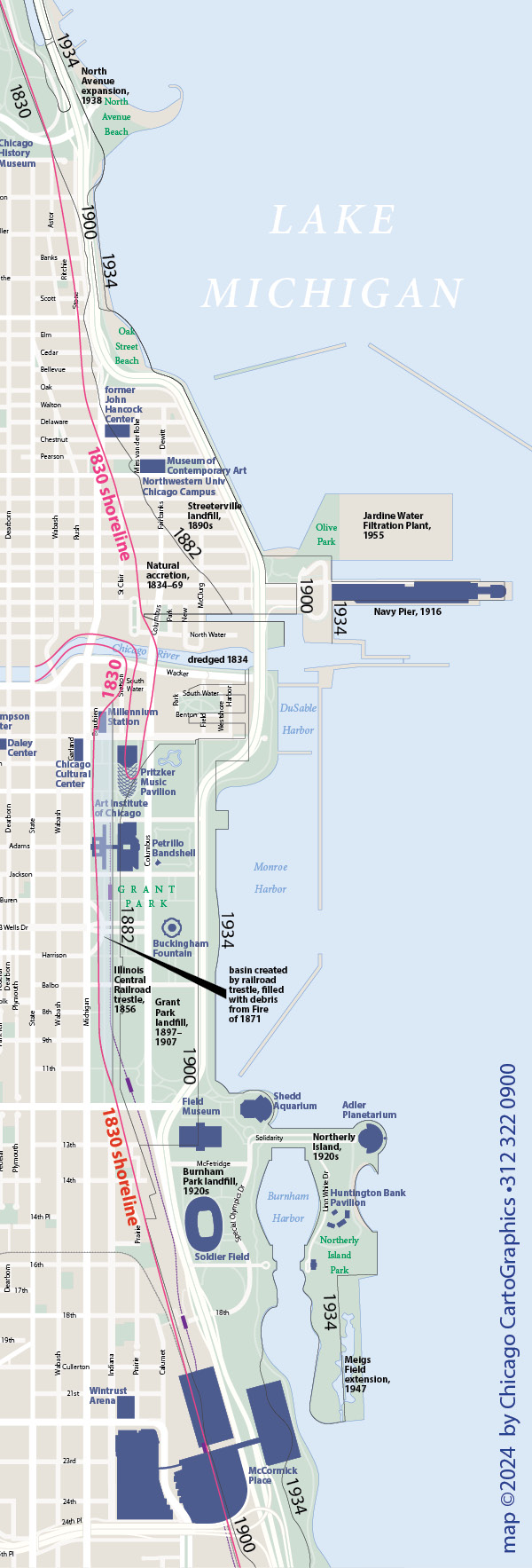

Chicago’s Lakefront Landfill |

|

Some 1800 acres of Chicago’s lakefront has been created by landfilling portions of Lake Michigan. The city was only 15 years old when the Illinois Central Railroad was given permission to enter the city via a lakefront route if they would construct a breakwater that would protect the homes and businesses along Michigan Avenue from winter storms. The railroad soon built tracks and warehouses by filling in portions of the lake, kicking off a legal fight that lasted decades. By the time of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the small lagoon behind that breakwater had become a stagnant backwater. It provided a convenient place to dispose of much of the rubble. The Lincoln Park Commission began enlarging its North Side park with landfill in the 1880s, and in the 1890s traded lakefront protection for riparian rights of adjacent landowners in a deal that created both Lake Shore Drive and new dry land that became Streeterville. The 1909 Plan of Chicago pointed out that the city was annually disposing of one million cubic yards of clean fill—mostly ashes from coal-burning boilers and dirt removed for basements—by dumping it far out in the lake. That was enough to create more than 20 acres of landfill if dumped close to shore. Park authorities eagerly adopted this idea in the 1920s and 1930s. Along the south lakefront, Northerly Island, Burnham Park, and Promontory Point were created. Lincoln Park, 450 acres when the Plan was written, was expanded to 1,200 acres by the 1950s.

The legal landscape of Chicago’s lakefront: It’s important to understand and distinguish the three different types of restrictions on building along Chicago’s lakefront: Grant Park, from Randolph to 11th Place, is protected by a deed restriction, the result of the platting of land in early Chicago. This is the famous “forever open, clear, and free” restriction Montgomery Ward sued to enforce, and is legally an “easement for light and air” that property owners on the west side of Michigan Avenue may sue to enforce against any buildings proposed in that part of Grant Park. Land that was once part of the waters of Lake Michigan, which includes much of Lincoln and Burnham Parks as well as the Museum Campus area of Grant Park, is protected by the Public Trust Doctrine. Much expanded in the 1970s for environmental protection, this doctrine forbids the transfer of filled land to a private entity. Finally, there’s the city’s Lakefront Protection Ordinance. All that requires is for the (mayor-appointed) Plan Commission to use its big blue rubber stamp as well as its normal rubber stamp. The Lakefront Protection Ordinance was easily swept aside when Mayor Richard J. Daley wanted the Childrens Museum in Grant Park, and also when Rahm Emanuel wanted the Lucas Museum. All of this is covered in some detail in Prof. Joseph Kearney and Tom Merrill’s 2021 book Lakefront: Public Trust and Private Rights in Chicago, which explains the legal underpinnings of Chicago’s unique public lakefront. |